Auxin Transport by PIN-FORMED1 proteins in Tomato

Auxin

I knew what I wanted to study before before I knew anything about plant biology: the evolution of plant shape. When exploring this topic, no matter what angle, I always bumped into the plant hormone auxin.

Auxin presence is linked to virtually every plant developmental processes that has ever been studied. Everywhere you look auxin presence plays a role in the establishment of how a plant lives, grows, and dies. Even more astounding, auxin is not just involved in these processes, but often it has been shown that auxin is directing these processes. Biologists are always curious about the start of a process, continually looking for origin, which is why I think auxin research intrigues many scientists. When looking for the first signal in all of my favorite plant developmental process, there is auxin. Concentrated auxin presence precedes leaf initiation, vein development, branching, flower initiation, and acts in countless other ways that make a plant, a plant. Every single species in the plant kingdom, and even some algae, are likely capable of transporting auxin to direct developmental processes that act in defining plant morphology. Auxin just has to be the right amount, in the right place, at the right time to direct these processes. The more we learn how auxin gets to the right place, i.e. transport of auxin, the more we begin to reveal how a plant grows from fertilization to the plants we see today. (see Resources for more details of auxin biology in plants)

Auxin is transported by PIN-FORMED proteins

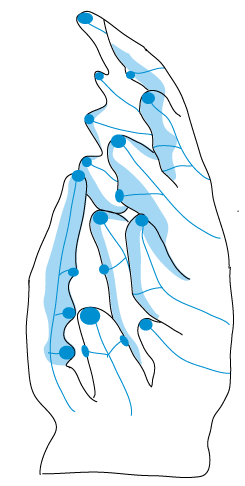

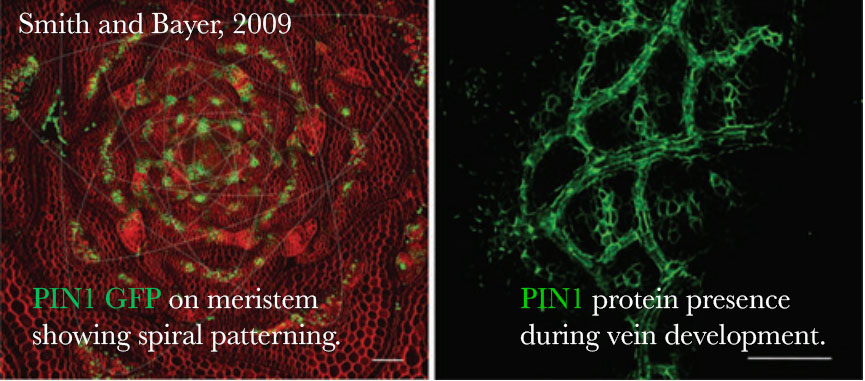

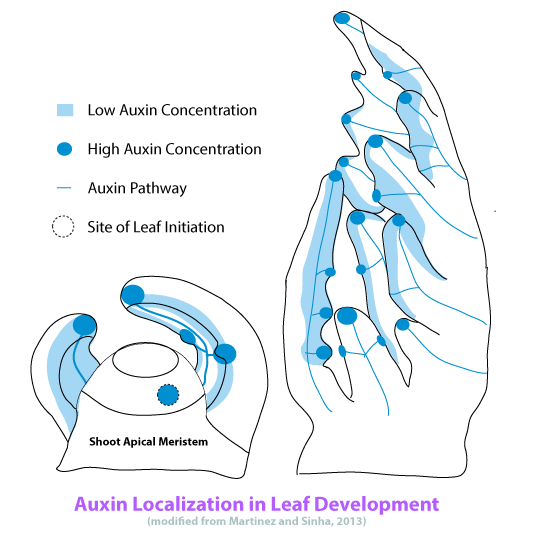

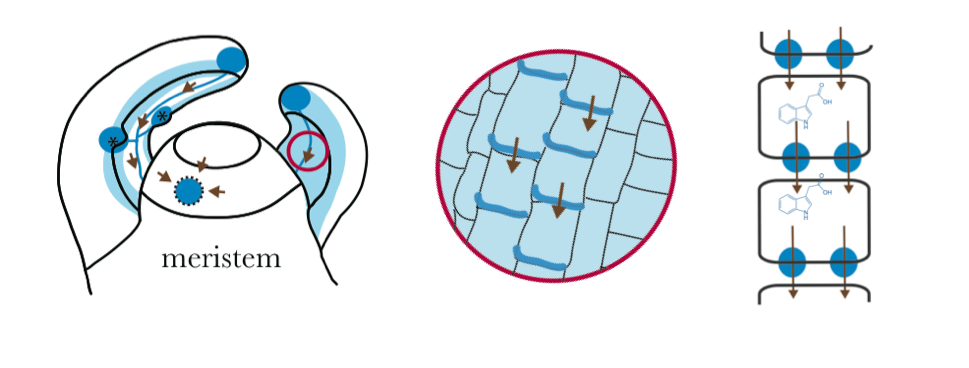

Some researchers describe auxin as acting very similar to substances in animals called morphogens. Morphogens were first described by a favorite mathematician of mine, Alan Turing1. Morphogens act in a concentration and spatially dependent way to signal cells to become more specialized. There are distinct patterns of auxin localization and auxin concentration throughout the plant, creating intricate networks of flowing auxin. For instance in leaf development, auxin flows from the tip of the leaf to the base, this auxin path eventually directs vein formation, creating the midvein on leaves. Spots of high auxin concentration and more diffuse auxin concentrations act to specify overall shape. The real cool questions, in my opinion, is how auxin can create these networks of auxin flow and how auxin get to the proper place to trigger all plant organs correctly. In addition, what are the similarities and differences in auxin transport across species? How did auxin regulation evolve?

One of the keys to understanding how auxin gets to the right place at the right time comes from studying a group of proteins called PIN-FORMED (PIN). PIN proteins largely determine where auxin is spatially because they are auxin efflux carriers, meaning they determine the transport of auxin out of a cell. Since auxin is passively taken into a cell, directionality of auxin is largely determined on the direction of auxin out of the cell by these PIN proteins. PIN proteins essentially dictate auxin directional flow by preferentially localizing on only one side of a plant cell, localizing on the outermost cell layer, the plasma membrane.

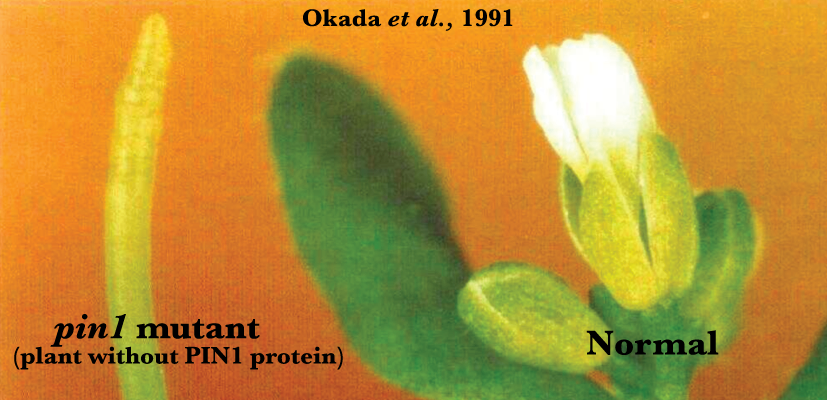

You can see the importance of PIN1 transporters by looking at what happens when you knock-out the function of the PIN1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana, plant biology's favorite model organism.

The Arabidopsis thaliana mutant is how the PINs got their name. The pin1 plants produce these "pin-like" structures because auxin is not able to regulate auxin concentration spatially, which noramlly specifys where to induce flower and leaf formation. You can even induce leaf formation on a pin mutant plant by applying auxin externally to the pin-like structure, as seen in this seminal paper on the influence of auxin on leaf development from the Kuhlemeier Lab (Reinhardt et al, 2000). These pin1 mutants can still react to auxin, they just cannot specify where auxin goes without the PIN1 protein.

Evolution of PIN1 function

The story of how PIN proteins, especially PIN1 regulates auxin transport has been studied extensively, but unfortunately, most of the work is in Arabidopsis thaliana. This is unfortunate because PIN proteins are thought to be present in every species in the plant kingdom, yet we don't know how these incredibly important proteins are functioning in these other plant species very well. Understanding how these PIN proteins function in other species will give us the evolutionary context to understanding how auxin contributes to the great diversity of plant shape in plants.

My work

1. What is the phylogenetic relationship of PIN1 genes across the plant kingdom?

2. There are three PIN1s in tomato, how do they function in tomato? Is there function different/similar to other PIN1 in other species?

3. What happens when PIN1 function is altered in tomato? What happens when there is no or reduced PIN1 proteins?

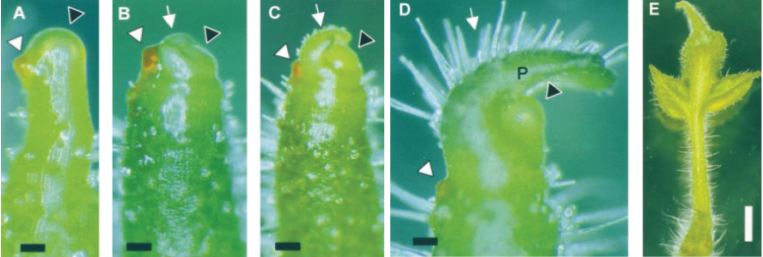

Our lab has found a pin1 mutant in tomato and through thorough characterization of this mutant, we can begin to understand how PIN1 function is similar and different in the plant kingdom. In addition, I have knocked-down two other closely related PIN genes in tomato to try to understand how PIN1 acts with PIN gene family member to regulate all the formation of plant architecture in tomato.

Resources

The Power of Auxin in Plants. free

Auxin transport-feedback models of patterning in plants. free

Origin and evolution of PIN auxin transporters in the green lineage. free

Book review:Everything you always wanted to know about auxin but were afraid to ask. book review free, book is not

1While morphogens are almost exclusively described in animals, and only recently (and hesitantly) used to describe auxin in plants, it is interesting to note that Turing's interest in this field came from his fascination with leaf initiation patterns, also known as phyllotaxy, in plants. Study after study suggests the key chemical involved in leaf initiation patterns is auxin! So that is one of the many reasons I like to consider auxin a morphogen.