The development of vein patterning in domesticated tomato and desert adapted wild tomato relatives in response to simulated shade

Plant veins

I was first attracted to the veins of leaves because it stood out as one of the more stunning developmental patterns found in plant development. Veins are also compelling from an evolutionary perspective; the acquisition of veins allowed plants to colonize land. Just as animals moved from the sea with the adaptation of lungs, one of the main features that allowed the colonization of land by plants was veins. Veins allowed plants structural support and a highly complex transport system. The more I learned, the more I found myself becoming increasing interested in the patterns of vein growth. The variability of vein patterning and density in the plant kingdom is immense. Go ahead and take a trip outside and look a closely at the leaves around you and notice all the differences in vein patterns that exist. What is the selective pressure that is acting upon species to establish the diversity of vein patterning we observe? This questions led me to start looking into one way in which vein patterning differs: vein density. Vein density refers to how many vein strands are present in a given area of a leaf and vein density varies considerably across the plant kingdom. But why?

We can split leaf vein function into three main areas:- Water Transport : Plant transport water from the ground to above ground using xylem tissue, a major part of the plant vascular system.

- Nutrient/sugar transport : Using the phloem tissue, the plant vascular system transports mainly sugars, which are the products of photosynthesis in the leaves to other parts of the plant where it is used for energy.

- Biomechanical Support : The veins provide almost a skeletal network providing a flexible support system for other parts of the plant.

What are the influences that determine plant vein density?

Some believe that higher vein density allows a plant to have more stomata per given area. Stomata are pores on the leaf allowing gas exchange. The rate of gas exchange is called stomatal conductance, and many studies have found a correlation between vein density and stomatal conductance, where leaves with more vein density have higher stomatal conductance. (Sack and Scoffoni, 2013)

More veins could also mean greater rate of food transport (nutrients and sugar in phloem).

Higher vein density could also lead to greater protection from herbivory damage. You could think of the vein network as a highway system. If a road becomes blocked, traffic will naturally start to use other routes. The more routes, the less chance traffic problems will arise by the closure of blocked roads, the same could be true for veins.

One of the more interesting hypothesis is when you think about it in the opposite way. Is there a benefit to low vein density? Are there environmental factors that favor adaptation by lowering vein density?

We are just beginning to understand how leaf vein density changes in response to environment. One factor in particular, which has been of great interest to our research group is shade avoidance. Shade avoidance is the mechanism in which a plant responds to neighboring plants. Since plants are competing for light resources, they have adapted to respond to this competition, many times responding by increasing plant height through internode elongation and an increase in apical dominance. Our lab is especially interested in changes in leaf development in response to shade and have recently found that tomato leaves can respond to simulated shade by increasing leaf blade area, but is there a vein density response?

System

The system we are using is the domesticated tomato (Solanum lycoperiscum) and closely related wild relatives of tomato that have adapted to drastically different ecosystems. I have focused on a desert adapted species Solanum pennellii, which in addition to growing in drastically different light environments compared to domesticated tomato, has differences in leaf shape and size, and as we are beginning to uncover, vein density.Main Research Questions Which I am Exploring

What are the vascular difference in minor vein density between Solanum lycopersicum (domesticated tomato) and desert adapted wild relative Solanum pennellii?

Is there a difference in minor vein density between species in response to sun and shade treatments?

Are there introgression lines between Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum pennellii that can explain the differences in vein density bewteen the two species?

Is there a relationship between minor vein density and leaf shape?

When in leaf development are the differences between Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum pennellii established?

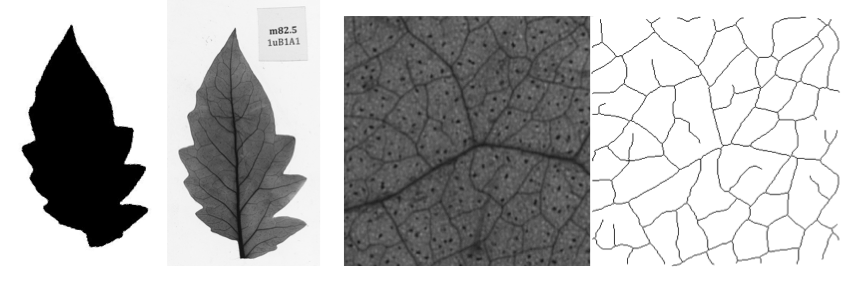

High-throughput Analysis of Minor Vein Density

In collaboration with Donnelly West, Jessica Budke, and The Tomato Interns.

In collaboration with the Maloof Lab, which studies shade response, we looked at vein denisty in both Solanum lycopersicum, Solanum pennellii, and 76 introgression lines (IL). Genetically, each of these IL lines is largely the tomato we eat, Solanum lycopersicum, but each line has a tiny genetic region that comes from the desert adapted species, Solanum pennellii. These lines can be used as a tool to further understand the genetic regions involved in regulating vein patterning by finding IL lines that are look differently than Solanum lycopersicum, giving us a chance to pinpoint the genes involved in these process.

In order to answer many of our questions we needed a high-throughput way to measure many leaves. We first cleared and stained the leaves in large batches using a modified freely available protocol from leaf vein experts in the Lawren Sack lab. We then used a high definition scanner to scan thousands of leaves. We then further calculated vein density using a combination of tracing and programs that aid in automating the measuring process (ImageJ)

There are significant differences in density between Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum pennellii. Not only are there density differences between species, but the leaves of these species also show a significant negative correlation between shade treatment and density, suggesting that the leaves may be capable of responding to light by increasing their vein density. This makes sense when you think about one of the main function of leaves, transport of water. In high light conditions, water is a valuable commodity, we can reason that plants have developed a response to the system that transports the water throughout the plant body.

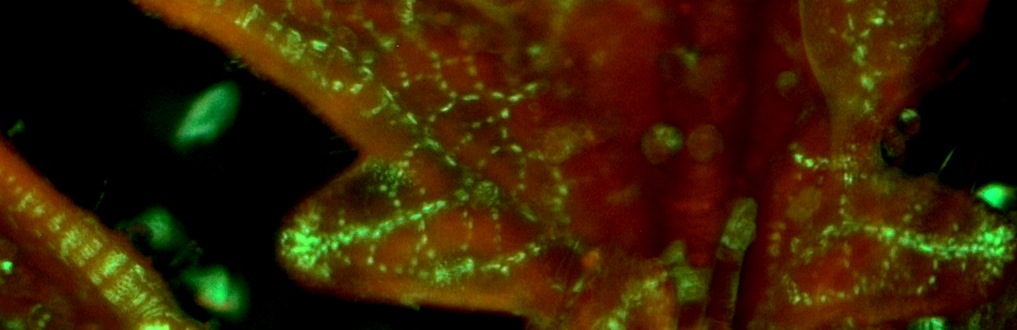

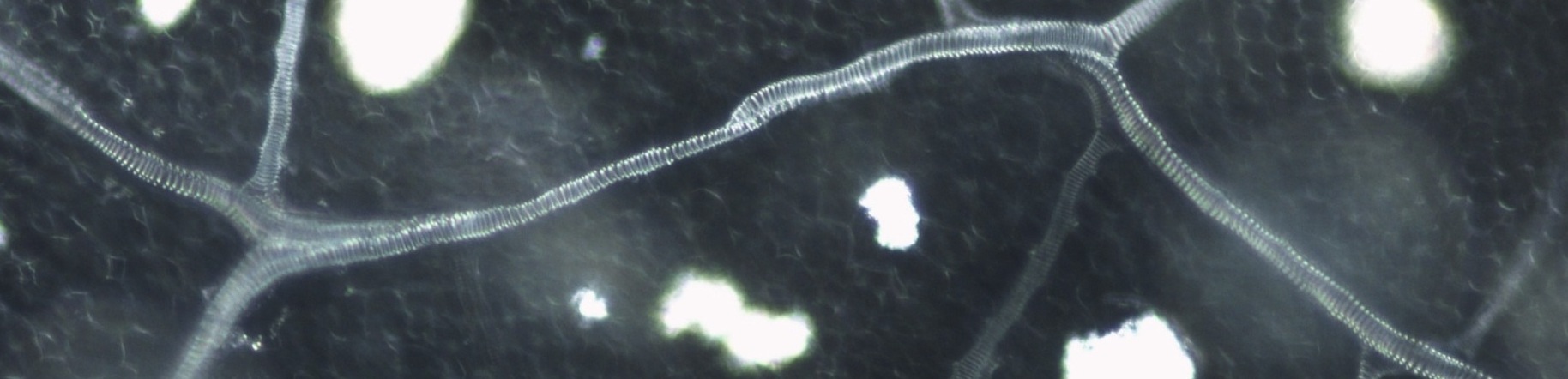

Developmental Timing of Vascular Development

We are further trying to understand how coordination of developmental timing and establishment of leaf veins is occurring, to investigate how and when the plant would be responding to shade. We already have a great understanding of how leaf vascular is established and the first signal to trigger vein differentiation is thought to be my favorite plant hormone, auxin. To investigate this, we are looking closely at when veins are established and more importantly trying to find when vein pattering stops in development between species. Is one species capable of responding to light treatments later in development than the other? Is one species capable of modifying vein density to shade better? These are questions we are currently asking by using a florescent marker that labels where auxin is present right before the establishment of the vein in three tomato species. This is my favorite part since my previous intern, Gillie Ish-Shalom, and I got to spend a lot of time taking beautiful photos of early vein establishment.